Mario Airò, Stefano Arienti, Maurizio Cattelan, Mario Dellavedova, Massimo Kaufmann, Armin Linke, Amedeo Martegani, Vedovamazzei, Luca Vitone

curated by Giorgio Verzotti

26 October – 15 January 2022

A Milan story

It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that it all started with an abandoned factory in Milan. The Isola district is now home to Stefano Boeri’s Vertical Forest, as well as many other new buildings that appeared during the Expo. But until 1984, there was, together with the Nuova Idea disco club which has now also disappeared, the Brown Boeri company or, more precisely, its building, as the locomotive and tram factory had already been relocated. The space was occupied by a group of artists who, in May 1985, presented themselves to the art public with a group exhibition that remained famous for marking a new beginning, for starting a disruption that affected the entire national art scene and beyond.

It all began with a group of young, self-managing artists all working in Milan, outside of the System. It is within this new cultural turmoil that

a new generation emerged, which included Stefano Armenta, Amedeo Martegani (both present in that first exhibition), Mario Dellavedova, Massimo Kaufmann, and many others.

We should point out that there were already other self-managed spaces in the city that worked with young people: the Care Of, in Cusano Milanino in the hinterland, and Viafarini, located in the homonym street, the first operating since 1987, and the latter since 1991. Not only did they organize exhibitions, but the two centers joined forces in 1995 to create a Documentation archive on young Italian artists, which became over time a crucial reservoir of information. The space in via Lazzaro Palazzi also emerged from the artists’ will, gathering a group of former students of Luciano Fabro, professor at the Brera academy; among them were Mario Airò and Liliana Moro, who will go on to receive wide recognition.

It was Corrado Levi who took them under his wing. A multifaceted intellectual, a professor of architecture, an essayist, a theorist of the gay movement, an art critic with a long family tradition of art collecting, a cultural agent, as well as an artist himself, Levi opened a studio in Corso San Gottardo. Here, the artists previously mentioned were exhibited, along with many others from all over the country: Maria Vittoria Chierici from Milan, Bruno Zanichelli from Bologna, and Pier Luigi Pusole from Turin. Levi’s work was going to create a shift within the institutions: in a city with no contemporary art museum worthy of its name, there was, however, the PAC, the Pavilion of Contemporary Art, some sort of Italian Kunsthalle, which in December 1986 entrusted the curator/artist with the exhibition “Il Cangiante.” For the occasion, Levi called upon some of those young artists, placing them face to face with history and internationality, from Otto Dix to Carla Accardi, from De Pisis to Jeff Koons.

Thanks to this creative generation, Milan returned to be a city of art, a propulsive and not only receptive place for new ideas. It had not been successfully done since Fontana, who died in 1968, leaving this primacy, in the 70s, to Turin and its Arte Povera movement. Starting in the mid-eighties, this sort of new Milanese renaissance had attracted several artists from outside the city who came to live and work there: Vanessa Beecroft and Luca Vitone from Genoa, Chiara Dynys from Mantua, Gabriele Di Matteo and Vedovamazzei from Naples, Maurizio Cattelan from Padua, not to mention the Milanese by birth, like Marco Mazzucconi and Armin Linke.

Where the artists are, the System works, and during the 90s, gallery owners also began to arrive in Milan. Young and determined people themselves, they did not hesitate to work with new artists, even though they rightly sought an international response from the very beginning, which would eventually arrive for many. The city became a meeting point, an opportunity for critics to meet Italian and international artists who came to exhibit in these spaces. This had not happened in years, except, of course, for the guests of the most historic and established galleries.

In short, the 90s made people forget about Milan’s Tangentopoli and transformed the city into a capital, at least in a cultural sense, but not only in relation to the visual arts.

What did these artists do, what did they put forward to become the protagonists of a new creative season certainly not limited to Milan, but that had found a meaningful space and area of engagement in that particular city? Truth be told, they were a very eclectic group: some had not even attended academies and were coming to the art world from all sorts of different paths. However, they all had a trait in common that set them apart from the previous generation, the protagonists of the Transavantgarde. For the latter, painting or sculpting were means of expressing their inner world, unconscious ghosts, and personal mythologies. More than expressing, our artists wanted to communicate.

For them, the artwork was a project resulting from an ideational path that took the form of a conscious proposition open to interpretation.

They also shared a common inclination towards more experimental languages, inherited from the neo-avant-gardes of the 60s and 70s, towards which, however, they felt no subjection. Indeed, their predecessors, the Masters, respected them but with a degree of detachment, perhaps because of their awareness of belonging to a different, more disenchanted era.

Examples of this attitude can be seen in the artists’ works present in this exhibition, which date back to those early years and, in some ways, reconstitute what was the creative landscape at the time.

Stefano Arienti re-elaborates pre-existing images. He is interested in re-creating rather than creating, and the iconography he addresses is that of mass-media production, the one that relentlessly bombards us with visual messages. The artist reacts by manipulating those images in a manual and direct manner implemented through simple tools and elementary procedures. Needles that puncture the figures’ profiles, plasticine applied to the printed colors, sculptures created by folding the pages of books or comic magazines in various ways. And again, images created with tracing techniques, with silicones applied to tissue papers. From the very start, Arienti had set up a playful counterpoint to the empire of signs and its power of enchantment. His manual re-elaborations, sometimes destructive using cutters or erasers, act as a revenge on the technique of serial reproducibility, a sort of strongly ironized humanistic fit.

A similar attitude is present at the roots of Amedeo Martegani’s early works, which reflected on art as understood as a noble matter, on the “great tale” of the Founding Value. We still remember his color reproductions of old masterpieces, modified with watercolor strokes to obtain Raffaello più Bello, Rubens Mutans, or Watteau Nouveau. The artist had also presented pictorial portraits of sculpted faces found in a royal tomb of the cathedral of Saint-Denis, translated into painting in the style of Richter or Polke, that is to say, presented as blurred photographs or as dotted printed images. All this, however, is redone in a deliberately approximate, imprecise, technically flawed manner.

The artist is self-deprecating, posing as a young man incapable to even imitate correctly. The “portrait of the artist as a young man” that Martegani proposed at the time was full of self-irony.

The spirit of Massimo Kaufmann, on the other hand, is different. Taking his experience as an art critic, he confronted himself directly with the artistic practice, working however in a cultured dimension and without giving in to the fascination of media images. The small triptychs of balance weights that we see in this exhibition refer to a classic topos of Italian paintings, the representation of the Annunciation, which the artist derived from old masters such as the Beato Angelico. The blue, red, and gold colors allude to the sky, the earth, and their union with the comparison between the Angel and Mary, while the weight of each object is related to the others in accordance with the golden section’s harmonic proportions. This iconography interested the artist as it conveys the idea of a new universe of meaning generated by an act of speech, the Annunciation, which qualifies and distinguishes Western culture.

Mario Dellavedova also stood out for his interest in language, or better yet, for the relationship between words and images that the artist constructs to bring about free associations of ideas. “Ahi, disperata vita” – Oh, desperate life – is the first line of a Monteverdi’s madrigal that conveys a precise meaning, which here becomes ambiguous, lending itself to different and unpredictable interpretations when those words are made up of colorful flowers applied to the wall (fake flowers actually, to accentuate the effect). Thus, the precious rosewood box with silver inserts that showcases the association between the syllables Gio and Ca invites us, at first glance at least, to indulge in pleasant pastimes or perhaps to not take ourselves too seriously…

For Mario Airò, the primary engine of his work is the affective sphere. The starting point for creation is always something that the artist happens to experience directly; more so, Airò’s works arise from the urgency to communicate what affects the existential sphere. The world investigated by the artist can be known through emotion rather than through rational thinking. The elements that make up his often complex works are intended as intensifications of pre-existing signs (images, musical pieces, film sequences) reborn to a new life. The artwork is for Airò a source of thoughts, open to the observer’s interpretation: it floats in the sea of meanings with a deliberate accentuation of its indeterminacy.

The VedovaMazzei duo (composed by Simeone Crispino and Stella Scala) also resorts to the most diverse techniques and use of everyday objects, which they reclaim by changing their sign with a more aggressive, mocking, sometimes provocative intent. They said to have found their name by coming across a broken cemetery plaque during a walk; they also said to have seen two birds colliding in flight in the sky and created a series of works from this accident. Whether that is true or not, their works often live in the realm of such random associations, like the barrier of used mattresses and the bicycle: a series of incongruous factors that allows them to elaborate free associations and pose as the scenarios of possible representations, as barely suggested narratives.

Luca Vitone, on the other hand, descends into history, determined to question it in relation to the social context of the places where he exhibits his works, which often originate from this very confrontation with the territory and its communities. His works are free of any idealism, aiming instead to highlight the contradictions of the social order upon which communities are built. While he works on the reclamation of popular cultures, such as music and singing by presenting sound recordings, he also documents the loss of authenticity of those creations by pointing out their ghettoization in the context of folklore and tourist consumption. In the works on display, Vitone thematizes what he himself defines as a topological loss, a collective lack of historical-political awareness, which he visualizes in his topographic maps turned against the wall and therefore illegible or utterly devoid of directions.

Armin Linke’s photography also carries out an investigation into reality. In his early years, the artist worked in collaboration with others; an example of this are his impeccable photos of Vanessa Beecroft’s performance. However, he since then began his investigation into the aspects of social life in a world increasingly conditioned and eventually dominated by digital technology. The images of the sex fair held in Milan are a prelude to this research that grew to accommodate almost twenty thousand images captured in over twenty years of travels throughout the “global village” as it came to be in the decades following the early 90s. All this, without ever ceasing to question the specific expressive and documentary potential of the photographic medium.

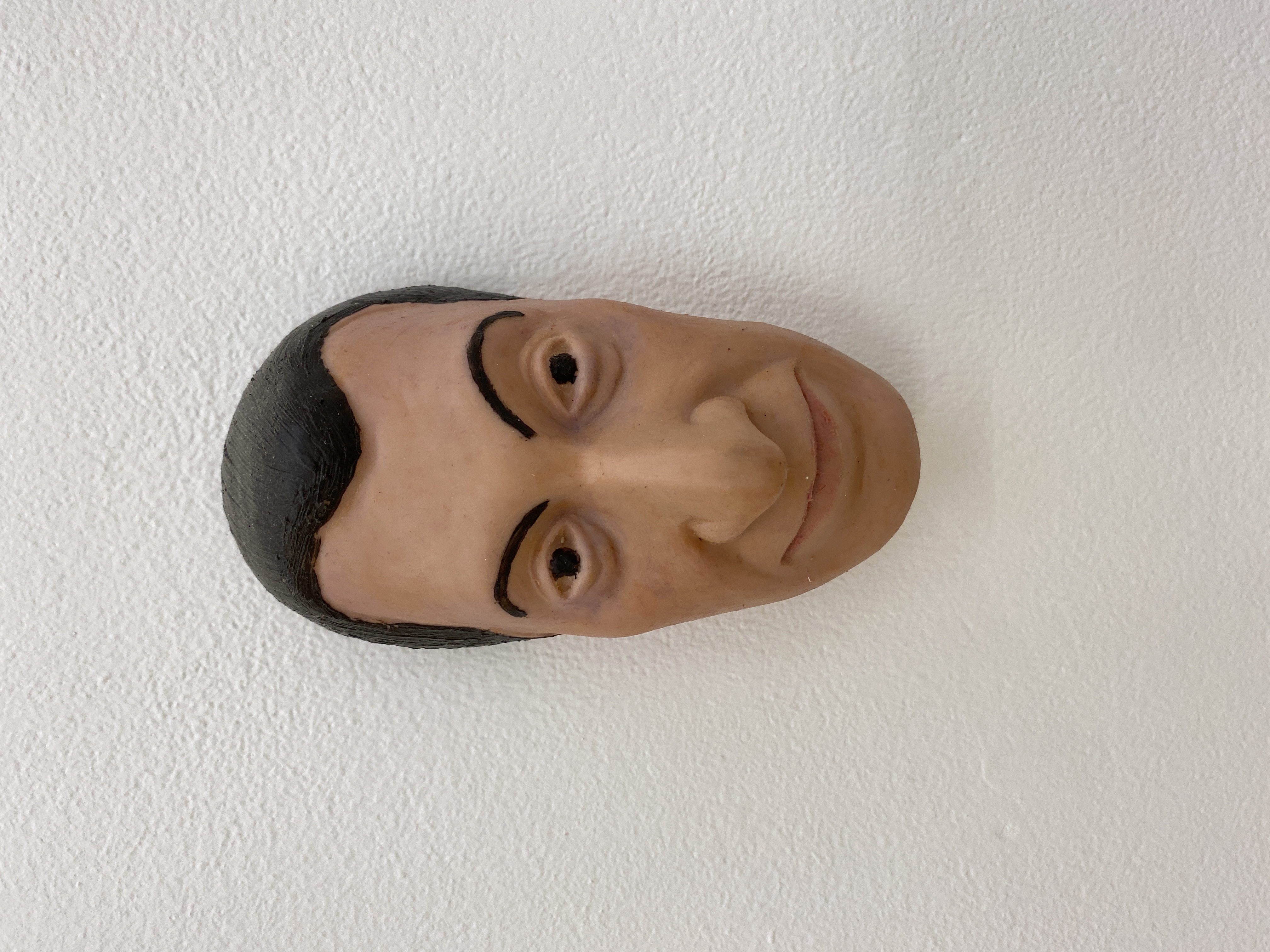

Maurizio Cattelan’s first endeavors can be defined as acts of information piracy that operate in the mismatches of the transmission systems of specialized knowledge, operating both in the macrocosm of socio-economic relationships, as well as in the microcosm of the art system, seen here as an integral part of the information system. In fact, the artist intervenes on the accredited values, on the devices of attribution of value integrated into such System, and on its rituals, with the intention of making fun of them all, starting with himself. On the one hand, he exploited the mythical aspects of the artist’s role, for example by forcing the gallery to close, and the gallery’s owner to find an alternative office, so that the teddy bear running on the wire (his artwork) could only be seen from the courtyard’s window. On the other hand, he has represented himself in self-denigrating terms with mannequins or latex masks, as in “Spermini,” where his miniaturized face is multiplied and scattered across the wall, creating something halfway between a carnival and a nightmare.

These are artists whose artworks, created within the 90s, are a testament to a specific era that took place in a specific city, with languages formed in a specific context, which eventually became the signature style of an entire generation, beyond the diversity of the elaborated content. Are these artworks still current? More than thirty years after their debut, have they maintained their freshness and initial innovative power? Do we still look at them today as curious, stimulating, and perhaps provocative works? Looking at their beginnings, could have we imagined such wide recognition for these artists?

In a sense, it is this “verification of powers,” the power of enchantment and belief that a work of contemporary art assumes, that motivates this exhibition. It should also be intended as an effort to create a sort of space-time détournement: to bring a piece of Milan’s artistic history to Palermo in a completely different social and historical context. The inspiration was Francesco Pantaleone, based in Palermo and Milan with an operation that surpasses a gallery’s usual commercial reasoning and becomes cultural offering. However, whether it is a valid one is not up to him, nor to the writer of these notes, to say.

As always, it is the public, the observers, who will give value to the artworks, to their historicity given the years that separate them from us, and who, with that in mind, will also judge the observations made here.

Giorgio Verzotti